Since I came of a responsible age, I spent most of my Thanksgivings at a swank New Jersey country club. I was a pre-teen coat-check girl.

It was my paternal grandmother’s job, really. She was the ladies’ locker room attendant in the summer and checked coats in the winter. Marginal though the jobs themselves were, they served their purpose. A symbiosis had arisen between my grandma and the ladies-who-lunch. They would give her bags and bags of their discarded clothes and other goods, which she would sort and dole out to her family back in the home country.

She never lost this instinct. Even though we were driving up from Maryland and not flying in from Jamaica, she would greet us by sizing us up and directing us to the appropriate closet. Low-rent though it was, long before the advent of "Black Friday," Thanksgiving for me was always a “shopping” day.

Racks and mounds of clothes weren’t the only luxuries introduced to us by the real housewives of New Jersey. I can’t think how long I walked around looking like nobody loved me at home before grandma introduced the concept of crème rinse. If my parents were just this side of hippie, my grandma’s house was decadence.

While I admit my tastes were always eclectic – they astounded (dismayed?) my grandma. There was the incident of the faux-wool-lined boots (my idea, and the last time we went shopping together); and the incident(s) of the more supportive undergarment (her idea, quite often, and quite insistently). The bewilderment grew as my tastes departed farther and farther from those of the princesses and discothèque denizens of Morristown.

Ah, but I only wore the hand-me-downs when I was at grandma’s. My old pedestrian cotton blends and jean skirts stayed folded in my luggage. Being in New Jersey was like taking a vacation from all that. I was in her world now. I went to the “spa lady” gym and did steam room while she put herself through some torturous conveyor belt contraption.

Thence to the club, where we made the rounds of her friends on the staff, and she deposited me in the coat-check room. She had coconuts to milk and goat to curry. I would enjoy the fruits of her labor the next day.

There were few rules. Special coat hangers for the furs. Don’t read the smutty novels (Try and stop me). It was easy work and I got a cut of the tips, which was more money than I knew what to do with. But the main thing was I got to be serious. There, wearing fashions that Muffy probably wore to that same event a year or two prior, albeit a little musty and smelling like Uncle Arthur’s cigarettes, I felt very keenly the responsibility to “represent.” Grandma, and my father, if they remembered him from caddying.

I wanted them to see that I was smart, that I knew how to act. I wanted, by performing a duty to her, to convey that she was the sort of person to whom people owed duties, that in her own context she was a matriarch. Plus, it was fun to watch their expressions change when they discovered the white girl was Vi’s grand-daughter.

I draw on these memories when people are talking about commercialism encroaching on Thanksgiving. For me, it always has, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way. Thanksgiving was the one time a year when I got to stand in Vanity Fair, wearing their clothes, guarding their furs, and think about who I am, who my people are, and who I want to be (and nick their chocolate mints).

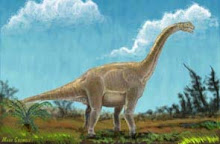

I was part of a movement of "dinosaur moms" when I lived in Maryland (Astrodon Johnstoni is the Maryland state dinosaur.) Which is nothing more than this -- dinosaur moms delight in the half-feral nature of the beasties they parent, even as they whisper Shakespeare and Kierkegaard in their ears at night.

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)